PORT Stephens beaches are vital for tourism and recreation, but sea level rise is causing beach narrowing, increasing erosion, and threatening local coastal infrastructure and recreational amenity.

Beaches are defined as sandy areas that extend over 20 metres in length, with their upper sections remaining dry at high tide, forming a natural barrier against wave action.

Rising sea levels have narrowed beaches in NSW, leaving no dry section at high tide and threatening shoreline stability and important habitat that supports diverse life.

This includes foraging and nesting shorebirds, nesting seabirds and turtles, crabs, and many small organisms that form part of the marine food chain.

Despite this, coastal development continues apace.

A historic look at our beaches

To understand changes to our beaches, let’s look at the wider picture.

Sand travels north along the eastern Australian seaboard, with sand from Sydney recorded at K’gari (Fraser Island).

This process formed Stockton Bight and the southern hemisphere’s largest mobile coastal dunes about 100,000 years ago and influenced the formation of the Port Stephens estuary.

Macquarie Pier built in 1896 joined the mainland with Nobbys Head, disrupting the northerly sand flow and affecting sediment supply to the north and to the Port Stephens estuary.

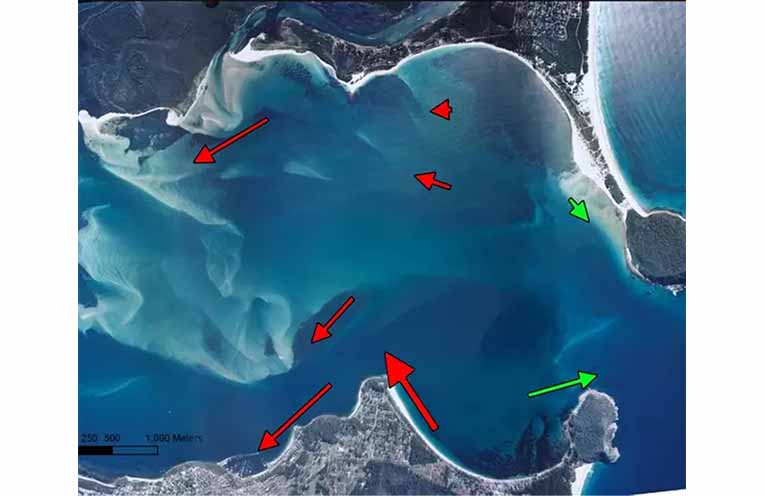

Port Stephens estuary is a dynamic Flood Tide Delta, where tidal currents deposit offshore sediment within the estuary, forming shifting sand shoals.

It is easily destabilised and vulnerable to change and erosion.

Northerly sand movement created tombolas and sand spits, such as the Fingal Spit, a once stable and vegetated spit, supporting a service road for Point Stephens lighthouse until destroyed by the 1898 Maitland Gale.

Similarly, Myall Point, within the estuary, east of Corrie Island, was lost during a 1927 gale creating Paddy Marr’s sandbanks.

Both these features were considered stable formations in their time.

Fast forward to today

The Yacaaba tombola, a low and exposed sandspit at the southern end of Bennetts Beach connecting Jimmys Beach to Yacaaba Head, is potentially extremely vulnerable to northerly storms.

If this tombola were to be breached, as seen at Fingal, the entire southern shore of the estuary from Shoal Bay to Soldiers Point would be exposed to damaging ocean swells and waves.

Four-wheel driving on this tombola exacerbates this vulnerability

Protection of Shoal Bay and Government Road is critical.

Proactive management is cheaper than reactive management.

Claiming the impacts are unprecedented does not hold as the climate crisis really bites.

Climate change at work

Beaches constantly change, experiencing cycles of accretion and erosion.

Typically, constructive waves deposit sand, while destructive waves remove it.

Rising sea levels have changed that; pushing waves further up the shore and increasing the impacts of shoreline erosion.

Warmer seas cause sea level rise.

The ocean absorbs approximately 30 percent of CO2 emissions and 90 percent of the resulting excess heat, storing four times more heat than the atmosphere.

This causes thermal expansion, which together with melting glaciers cause sea-level rise.

Beaches in the estuary and beyond all but disappear at high tide, reducing their recreational, economic and ecological values.

According to the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), every one centimetre rise in sea level results in a one metre horizontal loss of beach.

Since 1990, sea levels have risen by 10cm – corresponding to a 10m loss in beach width.

The loss of our beaches is climate change in action.

What to do about it?

There is no easy solution, but unmitigated threats posed by sea level rise and coastal erosion indicates that business as usual is not a viable option.

It is essential to move beyond reactive short term responses such as beach nourishment and develop proactive, adaptive management strategies, including commissioning studies to support modelling for future interventions.

Shoreline protection takes a variety of forms.

Hard engineering options like seawalls have a limited role.

They are outdated, expensive to construct, cause loss of beach and habitat and hinder beach recovery.

Eventually, seawalls fail (Manly, Bondi and elsewhere) and are expensive to maintain.

Nonetheless, some Council and coastal engineers still adhere to this outdated approach.

Rock revetment or rip rap walls are sloping installations of rocks designed to absorb wave energy.

The rock can be covered by sand, creating a back dune and an opportunity for propagation of natural shoreline vegetation further stabilising the system.

Similar structures can be placed offshore as emergent breakwaters.

These can be effective on open shorelines.

Sand can build up between the breakwater and the beach creating a salient and stabilising the system, however they impact visual amenity.

Geotextile sandbags, once considered a temporary measure, are increasingly used as a long-term solution.

They last about 10 years in sheltered areas but can degrade rapidly in exposed positions.

These are becoming a permanent feature at local beaches.

However, in combination with other interventions geotextile bags can provide more permanent solutions.

Beach nourishment involves importing sand from elsewhere and depositing it on a beach. It offers short-term stabilization but fails to address the underlying issues.

The introduced sand is eventually washed off the beach by wave action potentially smothering adjacent habitat such as seagrass beds.

Heavy machinery used for beach nourishment can damage and destabilise beach substructure and harm local ecology. The areas where the sand is sourced can also be heavily impacted.

Beach nourishment is most effective when combined with other interventions designed to address the underlying issues.

Nature based solutions such as revegetation is effective for natural shoreline protection but tends to be less favoured by engineers and councils.

Shoreline plants, dune vegetation, mangroves and seagrass can stabilise low-lying soft sediment shorelines.

However, rising seas and human activity threaten these ecosystems.

Coastal development replacing native plants with lawns destabilises the shoreline, while removing mangrove propagules from in front of beach houses further harms coastal resilience.

Mimicking natural structures such as shallow water offshore reefs that absorb wave energy using revetment style structures protect infrastructure and can stabilise beaches and vegetated back dunes.

With no indication that sea levels will return to “normal”, a paradigm shift in shoreline management strategies is needed. Every beach is unique and requires a unique intervention or combination of interventions.

A possible option for Shoal Bay

Erosion at Shoal Bay has been documented since the 1950s.

Through 1960 to 1979 vegetating the Tomaree tombola likely disrupted the natural wind-blown sand movement between Zenith Beach and Shoal Bay.

This led to severe erosion at the eastern end of Shoal Bay in the 1980s, and in 1994, Council dredged 55,000m³ of sand from Shoal Bay for beach nourishment, temporarily stabilising the beach.

Sand moves west along Shoal Bay, building up at the western end of the beach before spilling around Nelsons Head, as witnessed in the 1950s, 1960s, and finally in 2010/11 when it smothered the sponge gardens at Halifax Point.

Recent heavy weather eroded the western end of the beach, threatening Shoal Bay Road, resulting in emergency sand nourishment.

However, this is unsustainable without addressing the underlying causes.

Long-term solutions will require a combination of engineering (revetment), beach nourishment and revegetation to maximise dune stability and protect the road.

Offshore submerged artificial reefs (SARs) that mimic natural reefs are a possible option.

They have been shown to be effective nationally and internationally.

The Narrow Neck reef on the Gold Coast, built in 1999 to protect the Sydney-Brisbane highway, was refurbished in 2017 and is considered a successful example in Australia.

A SAR is a wide low-lying structure with a maximum height reaching below low water springs and positioned offshore from the impacted beach.

It is designed to absorb the wave energy before the wave hits the beach.

The reduced energy landward of the structure can allow sand to build up between the structure and shore, creating a salient (sand bar) which will help stabilise the beach.

SARs designed as multifunctional reefs can provide additional benefits such as offering combined beach fishing and snorkelling while protecting the shoreline.

SARs should be combined with other shoreline interventions to maximise their effectiveness.

The beach substructure needs to be stabilised, re-profiled and underpinned using revetment or alternative materials such as geotextile tubes leading into the back dunes.

This structure can then be covered with sand and the dune stabilised by propagating natural shoreline vegetation while the substructure and revetment will provide maximum protection to Shoal Bay Road.

Implementing these solutions will require detailed planning and modelling and significant investment but is more sustainable than ongoing beach nourishment alone and with a visually more appealing dune.

With rising sea levels and more intense storms predicted, proactive shoreline management is essential.

Delaying action will increase costs and risks to public and private infrastructure and to the local economy.

Rising sea levels and resulting beach loss has been a persistent problem in the Port Stephens estuary for many years and certainly cannot be described as unprecedented.

The problem demands urgent, planned responses, and is an obvious first step in local climate adaptation.

By Iain WATT, EcoNetwork Port Stephens